I had actually reached a rare calm the night before. Perhaps this was an unexpected reaction to the existential sanity of late period Mike Peterson in the utterly compelling court room-based Netflix documentary ‘The Staircase’. Peterson had served eight years in prison after having been found guilty of killing his wife whose death was actually apparently the result of a tragic accident. In keeping with the limited capabilities of the US legal system to entirely exonerate someone falsely accused, I was never entirely reconciled to his innocence. However, as presented by the end of the series, an elderly innocent man had come to accept that he couldn’t get that time back, nor fully clear his name, but that what mattered was acceptance and to make the most of what remained of his life.

Closing

down the i-Pad I stood and marvelled at the panoramic neon beauty of London, as

viewed from the top of a Leyton tower block. The vast visual sweep provided a

calming almost soporific effect. I cannot remember ever standing in this 10th

floor flat and feeling so relaxed in the still, almost silent urban beauty of

it all. I sabotaged this soon enough though in what I told myself was simply a

conscious choice to just be me and to see where that notion might go if I

imagined myself living alone with just virtual friends and a confessional

keyboard for company. In the middle of the night self-disgust fought for

control with a range of self-calming techniques. A couple of hours later the

imagined tight rein on the exercise addiction had gone very slack and, in the

almost light, I pounded the pavement en route to the Walthamstow filter

beds via a quick spot of self-flagellation at the public exercise machines in

an adjacent park. Running up the ten flights of stairs in a ball of sweat I

hurried back to bed in the hope of more sleep. A planned day of facing the

future by facing the computer screen, possibly punctuated by an overdue

haircut and an online discussion on Bahrain, didn’t help to relax me. The

thought of taking my push bike for an overland train journey to Penge seemed

a more appealing option.

The past is never dead. In fact it is always present. In George Orwell's '1984', O’Brien, the senior official who eventually re-programmes Winston Smith, gets him to incant: 'Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.' Winston Smith's successful treatment was for the alteration of memory.

|

| Memories aren't free |

I don’t know if my half dozen visits in recent years to my early childhood hometown are an attempt at controlling my past in order to re-shape my future. I just know that the attraction of revisiting Penge's remembered combination of freedom and claustrophobic conformity doesn’t fade, and that it especially grows when the present, let alone the future, seems far too difficult to contemplate. In the night I had remembered what it felt like as a boy to cycle away from home and to feel free, alone, on the roads and in the parks of the area. It was a strange sensation to be doing the same thing, at presumably greater speed, 45 years later. It wasn’t quite my childhood flashing back before my eyes, but I felt a peculiar rush as I raced past various monuments from my first 12 years. For the first time since I’d left Penge in 1976 I found that St John’s Parish Church, via which I had received something of a Christian education, was actually open. While not officially open to the public, the friendly female minister I spoke to outside and the welcoming Church volunteers inside encouraged me to take a look around, highly responsive to my expressed and seemingly open and honest desire to revisit the place that had evidently had a major imprint on me.

|

| Temperance & Hope, designed by the William Morris Co. |

|

| Chancel of St John's Church |

It was not like the emotion generated on my last visit to Penge when I had stumbled through a dark alley behind where we used to live. Nor was it like an earlier revisit when I felt child-like glee at once again seeing the dinosaurs ('Dinos') of Crystal Palace Park. Being inside St John’s Parish Church was to witness that the large, dark, almost foreboding chamber, full of stiff reverence and austere pews, had given way to a largely white space stripped of its rigid, hierarchical regimentation. What's more, the primary space of communal worship was now obviously much more accessible in both the literal and metaphorical sense. The imposing brass eagle whose spread wings had formed a lectern encasing a huge Bible was now unceremoniously parked in one corner of the seemingly unused altar. Pride of place though, under the stained glass of St John The Evangelist, remains the wood carving depicting The Last Supper.

|

| A more democratic space for worship |

The intricate stone of the original pulpit is now essentially a well-preserved reminder, to me at least, of a fast-fading past. I wasn’t saddened, nor exactly disappointed by what I witnessed though. I didn’t imagine St John’s Parish Church Penge would have the grand sweep of yesteryear. After all I am, physically and experientially speaking at least, much grown since I last entered here, even if I often still reside in my child. I had perhaps a greater appreciation for the stained-glasses than as a boy, noting their 'modern' beauty, and could freshly appreciate some other church features. The high-vaulted wooden ceilings, the beautiful arched doors, and the design of the baptismal font in which I had surely been dipped. This was incongruously located close to the exit where money-changing had once attracted me in the subtly-lit but long gone Church ‘book shop’. It didn’t look as if the baptismal font was still in use, surrounded as it was by dozens of folded chairs. That said, I am sure there are still Christenings at St John’s, so maybe.

|

| Baptismal font at St John's Church, Penge |

|

|

| The St John The Evangelist stained-glass |

|

Walking around the outside of the Church I was reminded of where my brother and me once rode our home-made go-cart, and of a surprising (even to me then) Church fireworks display hidden round the back. More poignantly, I recalled a never-forgotten dream experienced soon after we’d left Penge when I was flying around the church grounds like a large bird (an eagle perhaps?). Briefly revisiting the Rec for the inevitable cheese sandwich, I pushed my tired legs to carry me up, once again, to Crystal Palace Park. Sleepless the previous night I had had the idea that the resumption of my childhood mode of transport would connect me with something visceral from my past life.

|

| Fly like an eagle? |

Being back here again may have been an avoidance of necessary work on planning my future, but I continue to hope that returning will somehow reveal some deeper, and less dark, mystery from the past. Cycling up to the highest point of what had once been an exciting racetrack for motorbikes of a certain vintage, I prepared to revisit the high-speed childhood thrill of freewheeling home on a bike. For a brief period it felt the same as I once again raced down through the park, zipping past the now rusting splendour of the Crystal Palace Bowl, until sadly a cluster of walkers, some with barely controlled small children and even smaller dogs, necessitated me braking before taking a wrong turn and ending up in the Sports Centre car park. Perhaps as a boy I just didn’t care about interrupting the danger of racing round tight bends, getting a speed buzz at 10 that a man approaching 60 fears to do when so many other grown-ups are present. That said, continuing down the High Street at speed on a push bike still has its moments. An urge to scream as I careened down the street was, inevitably, repressed. I’d earlier once again tried to be gain access to our former flat above the High Street shop, but, 'Surprise, surprise, surprise, there was nobody home.' I didn’t try again.

I peddled

on past the old Police Station and The Pawleyne Arms, past the former secondary

modern, Kentwood School, and found, more or less, the location of a record shop

that, aged 9-10, I used to hang out in, pestering the sometimes indulgent staff

to play LPs by Paul McCartney and Hudson-Ford. The Clock House Station shops

are now the usual café, nail bar, tattoo parlour, hairdresser variety, and

quite a few are boarded up too. I couldn’t work out exactly where the record

shop had been. There was no point asking the people on the street in their ‘20s

or ‘30s if they had any idea. It might have been the site of the bizarrely

named and seemingly moribund ‘Geek School’.

|

| Site of Clock House bridge record store? |

|

| Or here? (Clock House bridge, Beckenham) |

I peddled

further and came upon Beckenham Library, an attractive 1930s facility threatened by the local council, located in front of the hideously

ostentatious 'Spa' erected on the site of Beckenham Public Baths. I remembered

nervously trying to swim there, watched from afar by my father. I needed a

place of rest, of inner calm. Inside the library I picked up a book on the psychoanalyst

Carl Jung. A section on dreams argued that these were different states of mind and not to be dismissed as just what happens when we're asleep. These could be revelations of

a different reality, of perhaps another version of ourselves.

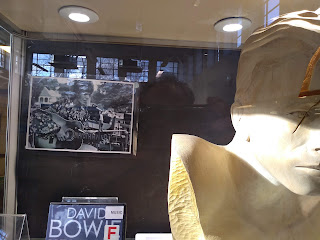

I then found

a shrine to local boy, David Bowie, including a well-made bust of the

man. Underneath that part of the Perspex

box dedicated to the global musical and cultural legend, were notes about the

present-day threat to Crystal Palace Park’s ‘Dinos’, a recognised UK heritage site

dating back to 1851. Next to the Bowie bust was pinned a black and white press

photo of a hippy-era David playing an acoustic guitar, presumably in Beckenham’s

Croydon Road Recreational Ground, evoking ‘memories’ of the free festival that he would soon immortalise in song. A little later I cycled furiously around

the same park, unaware that this was the location of the event that inspired

Bowie’s beautiful elegy to being… unchained. I was simply searching for a sunny

park where I used to escape to.

|

| Bowie at Beckenham Library |

|

| Bowie shrine, with a memory from a free festival |

In Beckenham’s town centre I found a kind of genteel respectability that was I think always there. The main roundabout is still dominated by the iconic Deco cinema where the whole family had once been moved by ‘The Belstone Fox’.

I cycled on and spotted a branch of WH Smith’s. What could be more mundane, if not borderline tacky? However it was here in 1973, at a little under 9 years of age, that the front page of The New Musical Express had screamed at me ‘Bowie quits’, reporting the ending of what later we’d realise was just one passing persona (Ziggy Stardust), as the end of the man’s entire career. That headline certainly caught my eye. I was very young, and the NME and David Bowie were probably more than a little forbidding. However, the idea of someone, whom I understood was himself relatively young and definitely out there, retiring had seemed amazing. Inside the dull almost empty inertia of WH Smith’s today I unsurprisingly couldn’t connect very much with that newspaper day of a half century earlier. I doubt if I knew then that he’d lived close by or had played (guitar) in the local park.

|

| Breaking the news of Bowie's retirement |

I rode back

to Penge, going once more along the exciting fast

road under the railway bridge. I’d once been driven at speed in the freshly

clean white Ford Cortina Mark II GT that had been my Saturday

morning responsibility for a few weeks. Alan, its 19 year old owner, sporting the

hair cut of a Bay City Roller (or so I thought), incongruously combined with

the then de rigeur brown overall befitting of one who ran a hardware store, had

somehow agreed to let this 10 year old clean his pride and joy. It didn’t last

long – too many smears on the windscreen for his liking. I doubt if I had been sod-casting

via my Ferguson transistor radio, but I vividly remember one morning cleaning the

Cortina and thinking intently of how much I hated 'Seven Seas of Rhye', the new

single release by up and coming band, Queen.

|

| Fast road to freedom |

I stopped

at a still familiar parades of shops opposite the old Kentwood School on the approach to Penge. I don’t actually recall

seeing the stuffed teddy emporium 'Bearly Trading' in its heyday, but whenever it

was trading it had definitely long since past. Not Trading at all. Beautiful brickwork

though. Cycling on I remembered the site of a petrol station that as a boy I

had visited in search of the renowned hurdler Alan Pascoe. According to the local

newspaper his flat had been located above, or close by. It was given, in what

was a very different era, as No 2 Kenilworth Court. I spotted the steps to

the self-same flats and remembered nervously climbing them, thinking of what I

would say to a medal winning hero of the athletics track. He wasn’t in,

however. Another familiar church offered an enticing message (see below) as I parked up

for another furtive cheese sandwich.

|

| Not even barely trading |

|

| The worried cyclist approaches the path |

Detouring

down Green Lane, I headed up Parish Lane, then journeyed along Lennard Road, once

again searching for places of sweet childhood memory. A nursery school where I began learning to ride a bike, my Mum looking on happily. A playing

field where I’d blagged my way into a private weekend event, scooping up masses

of strawberries and cream before heading out. All gone now. However opposite the

imposing Holy Trinity Church, soon to be united with St. John's, I found the half-hidden semi-gated walkway that connected to a tiny street of Edwardian houses. In recent years I have frequently revisited this path in my mind. It too cropped up in a childhood dream, and has somehow come to represent a transition to a different realm. I think this pathway

had created real fear for me as a child, but somehow it also embodied excitement, as if I could cycle between different emotional states, or more simply escape

into a different reality. I rode along the pathway, then carried my bike over the familiar enclosed bridge at Penge East

station, as I’d done hundreds of times as a boy, and peddled on.

Conscious that I didn’t want to be taking my bike across London on rush hour trains, I peddled back up toward Crystal Palace Park and specifically Penge West station. In minutes I was back into a different reality. The present, where the past is never far behind, and the future is just one step beyond. I had probably come to Penge to escape the future. My journey into the past had thrown up a lot of notions of escape, alongside some fear and also a kind of bravery. Knocking on doors (then and now), hassling to hear a record that I was never going to buy, getting the best out of strangers. It’s so hard to believe this version of events linking my past to my present, let alone perhaps linking to my future. I have to though.